PACTF 2019 Writeup: How’d I Get Hacked?

As I mentioned in this post, I wrote several problems for PACTF 2019, a cybersecurity and programming competition held for high schoolers. I’ve been asked to do writeups for each of the problems I did, and so I’ll be trying to do that—at least, where I think there’s something interesting to talk about for the people reading this who didn’t compete and don’t care about the contest.

Today, we’ll be going over “How’d I Get Hacked?”, which gives me an opportunity to talk about one of my favorite niche programming topics: the utter insanity and brilliance of Unicode.

The gist of the problem, for those that didn’t compete: there’s a bunch of filenames that look pretty innocuous, but something’s not quite right about one of them. You’re trying to find that one.

I’ll save you the time: even if you looked through every single filename, nothing would appear wrong. To see why appearances can be deceiving, we’ll have to talk about Unicode.

Unicode

When you read these words, you think of them as words. But computers don’t see words: they see 1s and 0s. How can we use bits to represent words?

One effort was ASCII, the system that early computers used. This system used 7 bits per character, which gives 128 slots for characters. This allows for punctuation, the uppercase and lowercase English alphabet, digits, some whitespace (like spaces and tabs), and some control characters.

This is fine for early computers in America, but it really does fall apart when you consider things like the enormous variety of other languages that use different scripts, the huge amount of symbols and punctuation that we like to use in computers (like math symbols or arrows), and emoji (yes, I’m serious).

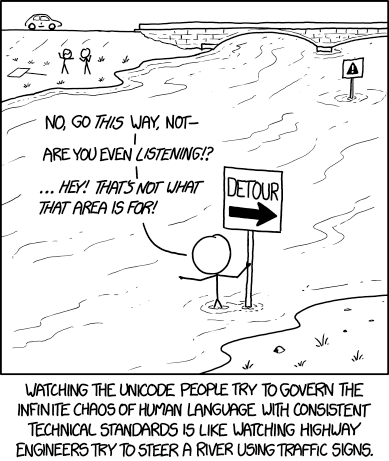

Enter Unicode, an effort to encode all of the world’s human languages into a language—bits and bytes—that computers can work with and understand. To a monolingual English speaker like me, that may not seem too difficult. But to anyone who has even a small taste of the true complexities that entails, you realize how insanely ambitious this project really is. The goal of the Unicode Consortium, the group that makes Unicode, is to make it possible to type, email, and text in any human language, even ones that aren’t spoken anymore.

Image is XKCD 1726.

A Quick Note on Rendering

Unicode is… inconsistently supported, to put it mildly. Almost any weird character errors you see on the Web are the product of bad Unicode support by programmers who usually assume things are a lot more cleanly cut than they really are. Additionally, rendering Unicode properly is really hard: it’s not bad for English text without anything fancy, but as we’ll see that’s a small subset of real Unicode. This means you might see different things from what I’m talking about depending on your browser and lots of other things: sorry about that, but there’s not too much I can do about it.

A Guide to Unicode Tomfoolery for Fun and Profit

Let’s go through some of this weird Unicode stuff, why it’s there, and how it might be used and

abused in other ways. Note that I’ll be writing the full hex code of the character like this:

U+HHHH, where HHHH is a four-letter hexadecimal code that represents sixteen bits. In Python, this

can be written in strings as '\uhhhh', so if you want to play around with this you can use

that. I’ll go from crazier to craziest, working our way up to the really weird stuff. Let’s get going!

Combining Characters and Multi-Character Graphemes

Quick grammar tip: the dots above the i in naïveté are called a diaeresis. This mark notates the idea that the vowel it adorns is prounounced separately from the one before it: the ai cluster is two syllables, not one. This is distinct from the umlaut, which is in other languages like German (some mathematicians have names with umlauts, like Kurt Gödel and Paul Erdös, and these names aren’t pronounced like other names with a normal o.

You can technically use the diaeresis in basically any English word with a vowel cluster pronounced as separate syllables. The New Yorker is, famously, basically the last publication to do this commonly, so you’ll see coöperate.

How do you represent words like naïveté in Unicode? Well, there are actually several ways. Unicode

does have code points (i.e., specific encodings) for some characters with an accent, like U+00E9 for

é. This allows keyboards to use this character, for example. But it also has a second system where

we combine accents with the unaccented character. This is useful for things like making Compose keys

work on keyboards, for example. In this system, you can use the U+0301 character, the combining

acute accent, after the character you want to put an accent on.

This creates some interesting ambiguities. How many characters does naïveté have? Well, it depends on how you write it! If you use the combining acute accent for the last letter, it’s 9: otherwise, it’s 8 (there isn’t a non-combining version of the diaeresis). Either way, when we ask about how many characters something has, we usually don’t mean either of these counts: we mean something called a grapheme, the smallest unit of a writing system.

If you want to have some fun, paste that accented naïveté into various character counters: see what they say! This is a good introduction to how any question about language is harder than it seems: deciding even how long a word is a very difficult thing to do.

Zero-Width Spaces

In some languages that don’t use spaces, like Japanese, it’s sometimes nice to use some type of

word-break character that doesn’t actually take up space on the screen. Enter U+200B, the

zero-width space: . (You probably don’t see anything between the space after the colon and the

period, right? Exactly.)

So how can we abuse this? One way is watermarking: imagine me giving you a document that looks normal, but actually has these zero-width spaces in them. If you leak that document to the press and don’t clean it beforehand, I can figure out that you were the one who leaked it because only your version of the document might have those invisible characters. (For instance, where are the two spaces I put in the above paragraph?)

Doppelgängers

Many characters in written languages happen to look very close to one another. The Greek question mark character, ;, looks an awful lot like the semicolon, ;. Many capital Cyrillic characters look exactly like their Roman counterparts, at least in some fonts: compare А and A or М and M. As you can imagine, there are lots of other examples: different kinds of spaces that can or can’t be broken across lines (to help aid line-wrapping for things like web browsers), different types of dashes, etc.

This can be used for watermarking, like above, but it has another nefarious purpose: because these characters often aren’t punctuation, they can be used in places punctuation can’t be used. For example, it can be used to fake a given website: instead of apple.com, you can use аpple.com, and in some browsers they’ll look nearly identical (they’re different!) (You can even get a certificate so the web browser says you’re “Аpple Inc.”, never mind that it isn’t actually Apple.)

Directional Overrides

The most interesting form of messing with Unicode for fun and profit is probably using directional overrides.

How is Unicode supposed to deal with languages like English that read left-to-right and languages

like Hebrew that read right-to-left? Ideally, it should be possible to have single documents with

both English and a right-to-left language, say if I were to include an Arabic quote on this

blog. Unicode solves this by using a couple distinct control characters: U+202D, the “left-to-right override”; U+202E, the “right-to-left override”, and a bunch of others for more specific uses.

This can be crazy: seriously, I’m not including any of these characters in this blog because I’m worried it will mess up the text on browsers. You can use it for watermarking, you can use it for forging specific words, and it has one other use that is really interesting and solves our little problem.

In Windows, a file is executable if its name ends with .exe in the order the characters have in

code, not how they’re rendered. However, file names are rendered correctly (otherwise, Arabic

computer users would have to read everything backwards). Additionally, some file managers and other

software will read the last characters as they’re rendered, and so they won’t notice this when

displaying the file graphically. When you also learn that these overrides are valid in filenames, a

very interesting attack opens up to us.

Let’s call the RTL override character ← for convenience, and so I don’t have to actually use these

characters. Let’s say I had a filename like qtdol←fdp.exe. How will this filename get rendered?

Well, everything after the arrow is flipped because it’s being read right to left. Thus, you’ll get

something that looks like this:

>>> print("qtdol\u202efdp.exe")

qtdolexe.pdf

(You can try this if you have a Python installation, copy the character into some other text editor, and mess around with it: it’s really fun and pretty crazy if you’re not used to right-to-left languages.)

This file looks like a PDF, but internally it’s actually an executable! This is the trick hiding in the PACTF problem: one of the files has this type of skullduggery in it, and so it’s the only executable file in the bunch despite not looking like it.

Takeaways

Some conclusions for any programmers out there:

- Unicode is really complicated: don’t rely on things like the length of text, text not looking alike, or the direction of text unless you’re really sure you know what you’re doing.

- Don’t take this as an excuse to not support Unicode, though: it’s not very nice to your users that don’t happen to be monolingual English speakers and whose names don’t contain things like accents. Use languages like Python 3 or Rust that have Unicode baked in by default if you can.

- If you ever want to really break a website, try inserting some of these characters into some text field and see what happens: the vast majority of applications don’t deal with this stuff properly at all.

Hope you enjoyed this: I’ll be continuing this with more posts about PACTF problems in the future. Stay tuned!

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus